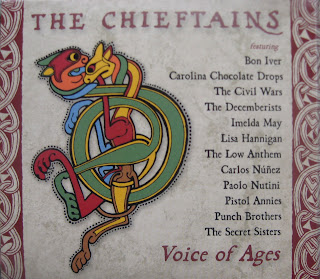

To mark their 50th year in Celtic Folk music, the time-honored, mostly instrumental group, The Chieftains, has just issued a special album titled Voice of Ages, with T-Bone Burnett co-producing. Once again the “lads” reached out to various vocalists to shape further or complete the chosen tunes. But this time the aging, Paddy Moloney-led Chieftains asked young folk performers (including Lisa Hannigan, Punch Brothers, Pistol Annies, the Secret Sisters, and the Carolina Chocolate Drops) to sing and play older selections from the British Isles tradition. Yet if you examine the credits closely, you discover a few exceptions…

The Decemberists deliver a rousing version--almost a call to arms--of Bob Dylan’s “When the Ship Comes In.” The quintet called Low Anthem in contrast doesn’t do much with Ewan MacColl’s thoughtful but tame number “School Days Over.” And hot duo The Civil Wars wrote a new song for the occasion titled “Lily Love” that sounds as old as “Peggy Gordon” or “My Lagan Love.” But one trackstopped me cold and prompted me to write this post—Scotsman Paolo Nutini singing “Hard Times Come Again No More.”

“All right,” I said to myself, “a fine performance of Stephen Foster’s major work, his social justice piece in the guise of a beautiful parlor song.” But when I looked at the publishing info, what I saw was “Trad., arr. Paddy Moloney.” I’d say that’s a bit greedy, even if legally accurate. Yes, the copyright no longer belongs to Foster or his descendants, but anyone who loves the song or happens upon it during yet another recession/Depression, would I think resent Moloney’s cavalier and unwarranted takeover; definite echoes of Led Zeppelin, the Rolling Stones, and other copyright skaters. Why didn’t Burnett or the record label (Hear Music, and isn’t that the Starbucks music spinoff?) speak up? I can’t imagine any economic hassles lurking when the item is over 150 years old…

Foster wrote “Hard Times” in 1854; he was only 28 but aware of the peaks of his earlier successes receding. “Susanna,” “Swanee River,” “Jeanie,” “Old Kentucky Home," "Camptown Races,” and other well-known sentimental ballads and minstrel songs and such, were already behind him. The nation was experiencing a recession (Foster too, and a separation from his family); there was a cholera epidemic in his Pittsburgh area and race riots in New York City. That year, minstrel show producer Dan Emmett put on the boards one "Hard Times," and busy fictioneer Charles Dickens (whom Foster had met back in 1842) serialized another. But the youngish pop songwriter didn’t need the elder pop novelist to inspire him; times were hard everywhere.

Foster rose to the occasion, producing lyrics that had a conscience rather than a broken heart, championing the poor rather than the rich, the “have-nots” rather than the “haves,” the 99 percenters with their noses pressed up against the glass rather than the one percent sitting enthroned inside—with his flowery language carried, and bested, by a graceful melody:

Let us pause in life’s pleasures and count its many tears,While we all sup sorrow with the poor:

There’s a song that will linger forever in our ears;

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

[Chorus here, then:]

While we seek mirth and beauty, and music light and gay,

There are frail forms fainting at the door;

Though their voices are silent, their pleading looks will say

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

There are more verses saying much the same, plus--following each four-line verse--this lovely, minimalist, personalized chorus reiterating sorrow and hope):

‘Tis the song, the sigh of the weary;

Hard Times, Hard Times, come again no more:

Many days you have lingered around my cabin door;

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

Foster’s vocal works have suffered ups and downs—picked as state songs, but picked over as stilted and sentimental; sung one year by world-circling African-American choirs, banned the next year as racist; his works grown so popular and familiar worldwide that they too quickly become “authorless” folk songs. But “Hard Times” avoids those issues and fastens on “the People United” as the best answer--caring and sharing and helping bear someone else’s burdens when trouble comes. These ideals (Christ’s own, for those who believe) seem to be beyond imagining for new-style racists-in-disguise, un-Christian fundamentalists, bought-and-paid-for politicians, and the sneering wealthy with their tax-avoiding accountants and private security forces. Whenever the economic picture or some social injustice sweeps the nation, or the globe, or now the Internet, someone busts out with “Hard Times”: revived, pertinent, comforting, back again.

The first recorded version came in 1905, an Edison cylinder from the Edison Male Quartette—haven’t heard it—but the first performance to be remembered was circa 1930 by the Graham Brothers, rescued from obscurity and made available on a Yazoo anthology CD titled after the song. (Variations found on this CD and otherrural collections—like “Hard Time Blues,” “It’s Hard Time,” “We Sure Got Hard Times,” “Hard Times in the Country,” even Elder Curry’s sung-sermon titled “Hard Times” as well—have nothing to do with Foster’s song.)

I can’t cite precise documentation but from the Depression forward there have been versions as diverse as--let’s say--Al Jolson and Nelson Eddy, the Sons of the Pioneers and Johnny Cash, the Robert Wagner Chorale and Thomas Hampson, fiddler Darol Anger (with Willie Nelson) and various American orchestras celebrating Foster as composer. (Two more who'd have done classic versions seem not to have in fact: The Blue Sky Boys and current fave Allison Krause.) But “Hard Times” reallycame into its own around 1990 when American citizens began realizing that bankers and CEOs, lobbyists and Right Wingers had co-opted and consolidated the public-interest media and quietly taken over the nation (Clinton having delivered other Corporate Demos right into the system too), and the gravy train had already left the station.

Among the better (maybe just bigger-name) versions I know of since then: the McGarrigle Sisters for a Civil War songs CD, Emmylou Harris live, and Mary Black with and without De Danann; all beautifully sung, all a tetch safe. Rather than a lullaby, I believe “Hard Times” can exhibit steely beauty, andbecome a rallying cry of sorts. For a tribute disc called Beautiful Dreamer: The Songs of Stephen Foster, the producers called on Mavis Staples, inimitable queen of Gospel Soul, and Mavis really soared—her rich contralto voice, subtle touches of melisma or note substitutions, and above all, her dynamics, the moments when emotion could break through… well, the excellent piano and guitar lines barely registered. Soul in hard times, thy name be Mavis!

Simpler but also worth examining are the versions recorded by Dylan (solo, on Good As I Been to You) and James Taylor (buoyed carefully by trio of virtuosi Yo Yo Ma, Mark O’Conner, and Edgar Meyer, on the CD titled American Journey). Next to themighty three, genteel Jamie turns stoic, subdued, close to affectless, while the players pluperfectly play on.

Meanwhile, Bob’s croak… I mean voice, has weathered, given up any pretense of innate musicality, become as cracked granite (occasionally chipped marble) rather than the grand cackle of his debut album and early performances, which startled the folk world squarely (or maybe hip-ly) into the 20th century. Here he sounds angry, tired, ironic, excited, determined… and still cool. In fact I would place this rendition--words and melody composed by America’s first great songwriter, sung (maybe “wrenched forth” would be more accurate) by the latersong master in as crookedly “straight” a manner as did occur for his much-dreaded Self Portrait tracks… yes, I would place Bob’s minimalist “Hard Times” right next to that tossed-aside masterpiece, “Blind Willie McTell,” his song honoring a different pairing of native geniuses--with the two performances together comprising the apex and epitome of post-Sixties Bob.

But the “Hard Times” continued. Early in 2010, at the star-fired "Hope for Haiti" benefit concert, big-voiced Mary J. Blige essayed her own soul-saving version, much in the manner of Aretha Franklin in her heyday--that is, start slowly, gradually wander further from the melody, scat sing a whole section, find the big finish. Solid vocalizing… albeit by the numbers rather than lived on the pulses.

And so to Bruce Springsteen: during the 2009 tour, in his street-smart, "Man of the People" mode, Bruce began featuring Foster’s parlor lament as the pause and lead-in to the rock-full-bore final section of each three-hour show. He stops the non-stop performing (and that’s just the mammoth crowd filling every inch of London’s Hyde Park) only long enough to announce Foster as the composer and America’s job-loss plight as quite dire. Springsteen’s arrangement (yes, he claims that legal position too) does in fact change or omit a few words, and find a mild tempo and tune that free the rock within, so his claim is somewhat justified. (But of greater significance is the heart-pounding concert created that day, a splendid record, so to say, of the E Street Band at its unified best, before the recent, unexpected death of sax “Big Man” Clarence Clemons.)

We’ve gone the long way ‘round… to arrive back at the most recent major performance of “Hard Times,” that of Moloney’s Chieftains and Paolo Nutini. As I suggested above, there’s much to recommend about this CD, from the sheer exuberance of elder Chieftains and young Turk folkies, to the grand and varied setlist, from the momentary magic of several performances, to the deluxe digipak presentation. But I am hard-pressed to approve this “Hard Times” in its Moloney disguise: an Irish dirge opening shifts to a lilting, regular tempo and a Glasgow Scot (of Italian heritage maybe) singing Foster’s 19th century, genteel-American lyrics, the voice multiplied by harmony overdubs. There’s also an Irish harp bridge, and finally a Scottish pipes band marches the tune away; all told, an arrangement that overreaches, trying way too hard to match the times and casual grace of truly Traditional folk.

But Nutini does sing all four verses, so we get to hear the fourth, which is often omitted and which reminds us to consider a worst case scenario:

'Tis a sigh that is wafted across the troubled wave;‘Tis a wail that is heard upon the shore;

‘Tis a dirge that is murmured around the lowly grave:

Oh! Hard Times, come again no more.

So… Stephen, Mavis, Bob, Emmylou, Bruce--you too, Paolo--answer me this: Why, oh why, can’t our Congress and Supreme Court just forgo all the hubris and learn to “sup sorrow with the poor”?

No comments:

Post a Comment